3. Discussion

The genus

Ilarvirus (family Bromoviridae) is composed of 22 permanent virus species, according to the ICTV taxonomy, whilst five tentative ilarviruses await official ICTV designations [

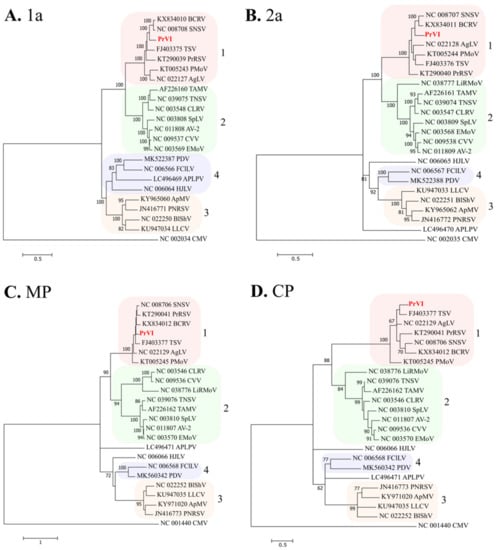

6]. From a phylogenetic point of view, ilarviruses are classified into four major subgroups: 1, 2, 3, and 4, whereas APLPV and humulus japonicus latent virus show no close relationships to the other subgroups [

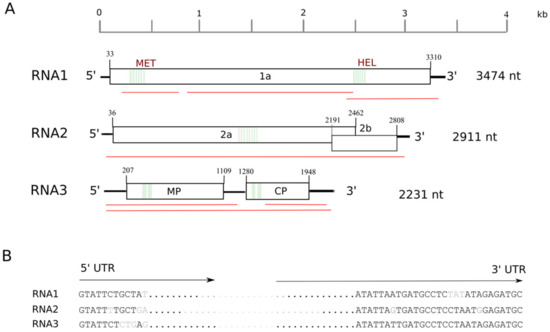

1]. Nevertheless, all the members of the genus share a few common features in their genome organization. The RNA1 is monocistronic, coding for their viral replicase (1a) and featuring a MET and a HEL domain. In subgroup 1 and subgroup 2 ilarviruses, RNA2 is bicistronic; apart from the viral polymerase (2a), they may encode a smaller protein (2b), through subgenomic RNA [

1]. Finally, RNA3 codes for the MP (proximal ORF) and the CP (distal ORF).

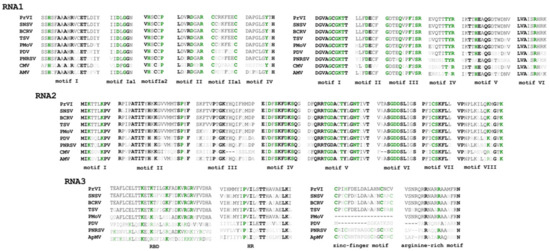

In this study, we characterized the complete nucleotide sequence of a novel ilarvirus from a sweet cherry tree, collected from Imathia region. Collective data from in silico analysis revealed that PrVI shares a similar genome organization with ilarviruses and harbors several motifs that are typical of the majority of members in the genus or even in the Bromoviridae family. Phylogenetically, PrVI is closely related to SNSV, BCRV, TSV, PMoV, privet ringspot virus, and ageratum latent virus, all members of the subgroup 1 of ilarviruses (). Therefore, PrVI consists the first ilarvirus from subgroup 1 that infects Prunus spp.

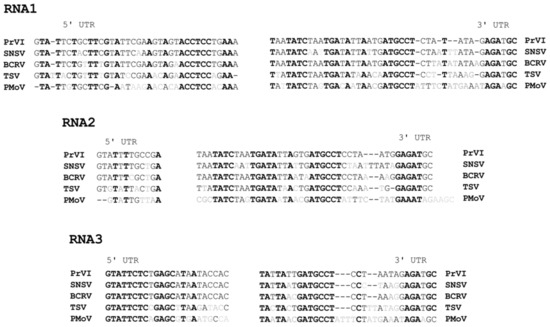

Furthermore, PrVI UTRs showed high nucleotide similarities with those of their cognate ilarviruses from subgroup I. A series of studies have shown that alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) and ilarviruses require the interaction of their own CP with the 3′UTRs of their viral RNAs to initiate replication and establish infection [

7,

8] and this function was termed “genome activation” [

9]. Interestingly, a highly conserved R residue located in the CP of AMV, citrus variegation virus and TSV, which is also present in PrVI () and two R residues in PNRSV, were shown to be crucial for this phenomenon to occur [

10,

11]. Altogether, the conserved nature of these residues in the CP of AMV and ilarviruses along with the nucleotide conservation in their 3′UTRs could facilitate this process.

A small-scale survey was conducted in Imathia region, which consists a major area of stone fruit tree cultivation in Greece. The purpose of this survey was to investigate the presence of PrVI in sweet cherry and other stone fruit trees. In this context, in 2019–2020, we collected samples from sweet cherry, peach and plum orchards as so to identify potentially hosts for PrVI and we used plant material from 2009, 2013–2014 from the collection of the Plant Pathology Lab (AUTH). PrVI was identified in a low incidence of 3.6% (4/138) in sweet cherries. Notably, PrVI was also detected in one peach sample. Nonetheless, further experimental data are needed to address whether peach consists another host for PrVI and, possibly, plum, as we only tested a small number of plum samples. Moreover, the virus was identified in samples collected during 2009, 2014 and 2019 thus indicating that PrVI is infecting trees in the area for over a decade.

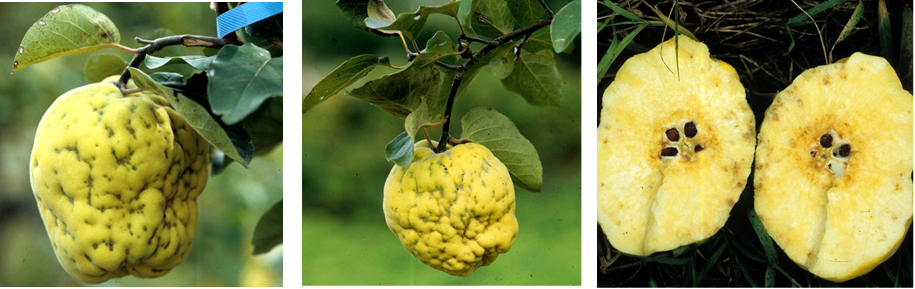

It is worth mentioning that the

Prunus samples that were found positive to PrVI, did not exhibit any obvious symptoms of viral infection. As fulfilling Koch’s postulates faces several limitations [

12,

13], especially in the case of viruses infecting perennial hosts, the implementation of alternative strategies to associate viruses with putative disease development, such as the simplified hierarchical approach proposed by Fox [

12], could provide a wealth of information on PrVI pathogenicity and this topic awaits future research.